Ndugu Chancler + Patrice Rushen: “1+One…4 Life”

Ndugu + Patrice Rushen: 1+One…4 Life

By A. Scott Galloway

Ndugu Chancler and Patrice Rushen are two of South Central Los Angeles’ most amazing poster artists for rising out of the L.A. Unified School District to achieve blinding heights of glory in multiple facets of the music industry then come and give back with generosity, passion and a master plan based on all they learned academically and in the field. Their collective resume essentially includes every major artist and professional situation an open-minded musician could dream of achieving – hit records, awards, band leading, composing, arranging, education, mentoring, coveted sideman/woman gigs, covers and samples – the list is long and fully deserved. It also includes them being in a band together called The Meeting with saxophonist Ernie Watts and bassist Alphonso Johnson.

Today, Chancler and Rushen are both educators at the University of Southern California (USC). Mr. Chancler holds the position of Adjunct Professor of popular Music and Jazz Studies. He has been teaching on the campus for 19 years. Ms. Rushen is the Chair of the Popular Music Department and just saw her first full graduating class this month at the close of her fourth year in the position which is the current life of the program – 4 years-old.

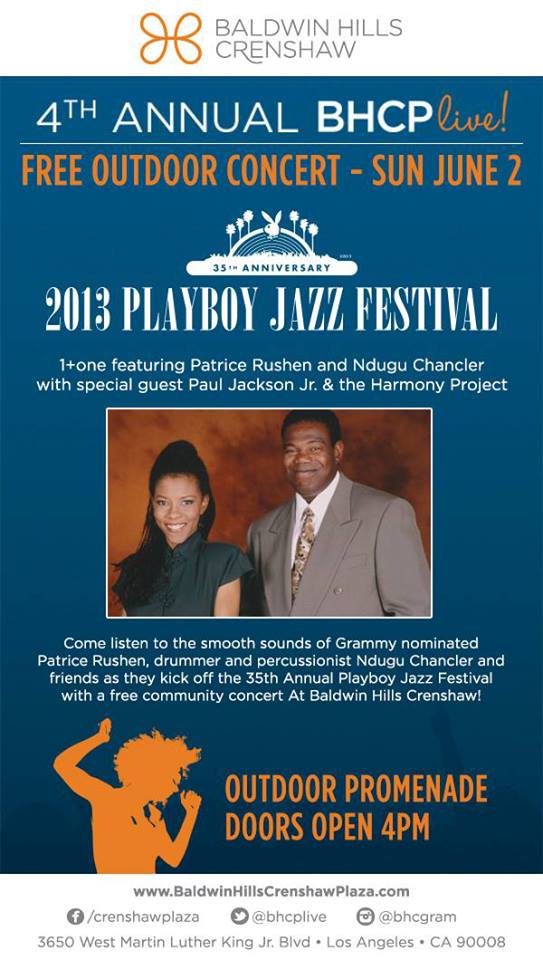

On Sunday June 2 in a FREE community concert at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza that is also tied in as pre-promotion leading up to this year’s Playboy jazz Festival, the duo will pool their talents within an ongoing performance project they started in the late `80s which they call 1+One – a synchronistic partnership that enables them to fully express the breadth of all their passions and masteries in music. Just returning from Germany where they did shows and some live recording (with bassist Rhonda Smith – formerly of Prince’s band), Ndugu + Patrice will play as a duo (naturally and with pre-programmed tracks) as well as with guest musicians Reggie Hamilton on bass and Paul Jackson Jr. on guitar.

In anticipation of this homecoming of sorts, I interviewed them separately about music education and their long-standing ever growing relationship as friends, musicians and educators. I got WAY more material than I was anticipating for this piece. So let’s just say this is Part 1…like a James Brown jam or a Chick Corea children’s song –BOTH of which these greats could handle with ease.

A. Scott Galloway: How did your relationship begin?

Ndugu Chancler: We started out in school. We built a strong nucleus because we used to practice just the two of us – together. We started to build a whole conceptual architecture that made a close unity. Then we developed that unity in other situations – with other people and with our own things. It’s always good to build relationships with people that you have similar background and are coming from the same thing/pace. I look at our relationship like Wayne (Shorter) and Herbie (Hancock). Over the years they’ve been in so many situations together, they bring a certain thing together to whatever they do.

Patrice Rushen: Our friendship goes back to summer of `69. I had gone to Henry Clay Junior High and Locke was a brand new high school. Prior to Locke I would have gone to Washington High. That summer when they reformed all the boundaries in terms of public schools in the area, I was right on the boundary of going to either Washington or Locke. I went to Locke in 10th grade because I lived on the side of street that determined that’s where I was going. The other benefit was I went there for a summer program in `69 to be in Honor Band – a symphonic band in which I played flute. I met a lot of people who were attending or going to be. Leon Chancler was one of those musicians in the percussion section of the Honor Band.

This program just blew up in terms of musical activity and a new consciousness about what was possible once you had kids who found a certain level of passion in what they were doing and how that could be applied to everything. There were some very forward thinking young people teaching there at the time. Reggie Andrews was one of them. Music was used for us as a tool to motivate and inspire us to do well in our other classes so we could take part in all these great music activities. A lot of students formed life-long friendships and bonds. And it wasn’t just my class. There were a couple of classes before me and several more after me. That kind of thinking may sound obvious today…like, “yeah that’s what we do.” But at that time – especially in the Black community – that was another thought process altogether. Music was taken seriously as a powerful gateway. We were in Watts – post-riot. They did not want kids falling prey to being in the streets having nothing (constructive) to do. Besides, we had the biggest gang going. If you were in Marching Band, ain’t nobody messin’ with you!

We had two of the finest music teachers that L.A. Unified has ever seen: Donald Dustin and Frank Harris. Then Reggie came along and he wasn’t that much older than us so everybody was really in tune with whatever he had to say! He handled the majority of the activities relating to us as African Americans to the contribution of our people to the music of this country. It gave us a certain kind of pride in the music. We learned about jazz, rock, pop – all through the lens of being branches from the same tree. One in which African Americans had not just contributed but were the architects of. We still had concert band – we were still playing traditional high school repertoire for Concert band and Orchestra. Then we had the workshop which was the jazz band. We had choirs and we had the marching band.

That marching band marked my entry into arranging. That was the one area where we did not want to just have to play stock repertoire. We knew the tradition of the Black marching bands of the south so you know what that’s about. To do that, we had to be current with the music. So he challenged us. “If you want to play James Brown, somebody needs to write the music.” I don’t know why my hand went up but I learned to write and do those kinds of things that we heard on the radio and adapt them to marching band. Then our steps would make sense. I stepped up for that in my second year. So I did that and Ndugu led all of the drum cadences. Once we were challenged in things that we really cared about, we were also given the tools and way to apply the tools. That gave us on the job training in an environment in which we were being supported. They didn’t just throw us in the deep end and tell us to figure it out. We’re showing you that stuff through the music we’re playing in concert band – Quincy Jones and Thad Jones charts that were way over our heads – but in that music are the tools you need to do what you wanna do with the music. You can start by filling a need and being of service. If you want to have these kinds of songs then write these kinds of songs. Make the music that you feel is missing. That was a MAJOR GIANT-SIZED seed that was planted in all of us.

Galloway: My first recollection of you two recording together is Patrice’s debut album, Prelusion (Prestige – 1974).

Chancler: Prior to that we had worked with local guys and others – a blues guy named Little Johnny Taylor (big hit: “Part Time Love”). I remember us going up to Oakland and playing blues with him. Then we were on different sessions together for Fantasy Records. Some producers would even call us together for sessions. Then we started doing our own things.

Galloway: How did this simpatico bonding project 1 + One begin?

Chancler: That happened around 1988/1989 – right after we played together on a tour with Carlos Santana and Wayne Shorter (along with bassist Alphonso Johnson, percussionists Chepito Areas and Armando Peraza, and organist Chester Thompson). We were deciding what to do next. That’s when 1 Plus One started.

The concept was growing from the brink of the technology at the time. That was over 20 years ago. Groups were going out as two guys. We wanted to do something that utilized new technology but also free us up to do things that people couldn’t see us do consistently before. Without having a bass player we were free to play all the styles we wanted (ones that were weren’t always available). It was a new idea based on us and the technology at the time. We never did a recording under the name 1+One but we’ve done some pieces with that concept on our albums. Mine was Old Friends New Friends (MCA – 1989) and on her album Signature (Discovery – 1997) we did a couple – one was called “Oneness.”

Rushen: 1+One was Ndugu’s brainchild. We’d become increasingly frustrated because there were situations where you’re in a group and you have to lean all of the misc toward only one thing. Sometimes you lean the music in a certain direction because that’s what the leader wants to do. Then you’re called for something else and the music leans in another direction. Both are fine. But the music that we are about is music that involves a lot of different things. And every time we would try to put bands together, it would be increasingly difficult to find musicians available to get together and play where you could throw out anything and stylistically it would be an authentic expression of that. His person can do this but they can’t really play that. It’s really great if you’re grooving…but if you decide to do some straight ahead you’re like, “Naw, can’t really do that.” It became frustrating putting things together. Not that we couldn’t do it but it was a big deal. We’re like, “Dude! We just want to get out and just go play on occasion.” And at the time there were places where you could just play – no big production.

This is before computers but we had hard-wired sequencers that if you programmed the music in, you could play it back in real time and play along with it. Our performances on top of the sequencers could be the variable of wanting to be spontaneous. The discipline and the spirit of the groove were not going to change on the basis of who was holding down the bottom because those elements were programmed. We did all of the programming – I did 90% of it. That would determine then how Ndugu could get up of the drums and play vibes and I could get up off the keyboards and sing. Now this was before playback tracks. We’re talking early `90s I believe. There was no iPod or even a computer. When we started it was people taking small sequences of music and put them into a hard-wired hardware sequencer with a big giant disc. Yamaha made one – we were both Yamaha endorsees – a QX1…and programming it was like watching paint dry. It was a whole lot of equipment which was the drawback. You needed all these tracks for your keyboard sounds cuz it wasn’t digital audio. It was 1s and 0s triggering synthesizers. I had TWO TRACKS so that when the 1s and 0s came up…ALL of the sounds would be represented. They were a pain the butt on that tip! But freeing on the musical tip cuz we could go from straight ahead to “Forget Me Nots” in the same set. We could have a good time and talk. We had to be really coordinated in terms of timing – no different than in a typical contemporary pop show – but our jazz sensibilities were also served because we were playing whatever we wanted on top of it.

We were able to go to Japan. We did a lot of demonstrations. The concept at the time was really new. I could play timbales and drums and other stuff. It was really cool. We had a standing gig and were really able to perfect the show. Then we had to start figuring out how we could move this bad boy around. After so many years, we found ways to make it easier to do. It took about 20 years. But now we can do the same show with much less gear because now we have computers, iPods and stuff. We’re constantly in a state of having to convert things but ultimately stuff is more compact and easier to move around. However, it enables us to play a myriad of music but it doesn’t replace the magic that happens when you play with people. One of the nice things about having friends you grew up with is there are ways to be able to integrate more and more of that into the set because everybody speaks the whole language.

Galloway: You’re tapping into that same energy in your roles as educators now.

Rushen: No question. The challenges that Ndugu and I face even now as musicians and educators we’re able to pass some of that thinking on. This is very new for USC to embrace the concept of this music being able to have pedagogy – being able to graduate a musician whose focus has been on the popular and contemporary side of the music spectrum. This is something that is done every day when you talk about classical music. But with the exception of Berklee College of Music in Boston which was the first t adopt the idea that this music could be broken down and taught. We’re finding that so much of the information that I am able to pass to the students and a significant amount of the way I approach teaching the students has to do with the way that I was introduced to the music. There was a lot of experiential stuff happening. The instruction was cool – the information. Then there was the demonstration of the information, then your participation as a student to first imitate and emulate in order to get vocabulary then be able to expound on that. That is no different from the philosophies that were involved in my learning classical music, and studying piano.

Chancler: Music is the history of the world so you’re educating the socio-economic history of the world. Basically all I’m trying to do is give people the lineage and have them make the connection for themselves. When I was going to college, a performance degree was just a piece of paper and you could do absolutely nothing with it. So my degree was in Music Education. I was already being trained to do that whether I wanted to do it or not. Everybody thinks education is just in school but education is experience and apprenticeship. I learned as much in school as I did working with Miles Davis, Quincy Jones and everyone else. You put all that together formulate that then you create a place to bring that education BACK to the school. I had already been doing workshops, clinics, and summer jazz camps, so I had already formulated the curriculum which made it easy for me to just go to the school and put that to work on a day to day basis.

Our classes and curriculum often cross. Patrice and I are a team. Wherever we are, that’s always going to shine through.

Galloway: With you two coming from Watts/South Central Los Angeles and with this show performed in the once predominantly Black (now more Hispanic) Baldwin Hills/Crenshaw area, is it important hat your music express an African American cultural viewpoint?

Chancler: The African American cultural aspect is just natural – that’s who we are. But we grew up doing all these different things – that’s what we do. We don’t put labels or make a big deal. We’ve done R&B, Jazz, Pop, Fusion – that’s what we do. Music is a reflection of people’s own Diaspora. When you really tap into that, it’s always there. We don’t make a big deal out of being African American and pulling from that experience. Too often we try to put labels on certain things that we lose sight of who we are and what we’re doing naturally.

A. Scott Galloway

Music Editor

The Urban Music Scene