The Drums Will Speak of Legacy at Playboy Jazz Festival 2017

Drummer Carl Allen To Salute Elvin Jones and Art Blakey at Playboy Jazz Festival 2017

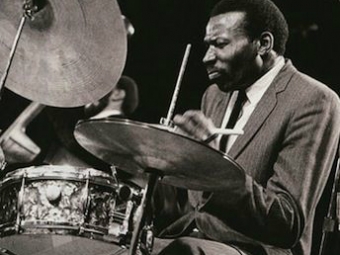

One of the true jazz highlights of this year’s Playboy Jazz Festival will be drummer Carl Allen wearing his bandleader hat fronting a band that will pay tribute to jazz drumming immortals Art Blakey (leader of the legendary Jazz Messengers band- a school through which scores of then-young lions such as Horace Silver, Donald Byrd, Wayne Shorter and Lee Morgan graduated with flying colors) and Elvin Jones (the mercurial titan most famous for being a member of John Coltrane’s classic quartet – including A Love Supreme – and as a leader in his own right). Allen – a coveted sideman, leader and educator – speaks emotionally and candidly about Mr. Blakey and Mr. Jones in the insightful piece that follows. He is also proud to announce that DW Drums is customizing a signature parade drum with a marine pearl finish to his specs and in his honor. Respect!

A. Scott Galloway: What brought you to the drums?

Carl Allen: I don’t believe we choose an instrument. The instrument chooses us. When I was a kid, I saw people playing English horn, oboe and bassoon. To me, these did not seem like cool instruments to play! But I learned that the people drawn to those instruments loved them just as much I love the drums. I felt a connection and couldn’t imagine playing another instrument. My mother told me that the one reason she finally relented and got me a drum set was because it was cheaper than constantly replacing her pots and pans I kept tearin’ up! The other reason is because I always wanted to do everything my oldest brother did. He was like the man of the house for me. He took drum lessons but not very seriously. His sticks were always lying around so I started picking them up.

Galloway: Did you gravitate to jazz first?

Allen: No. I came to jazz through a side door. I grew up playing R&B, Soul and Gospel. Then, in a strange way, I became very interested in drum and bugle corp. Another older brother, Eddie Allen, played trumpet and started giving me albums to listen to. One was Harvey Mason’s Marching in the Street (Arista – 1975). He had this rudimental thing going. I was taking lessons at the time, working on my rudiments. I heard the correlation in what Harvey was doing as well as Billy Cobham (A Funky Thide of Sings – Atlantic – 1975) which sent me down the fusion road. Eddie was twisting my arm to get more straight ahead records. So I bought one by (saxophonist/arranger) Benny Carter for 50 cents. My allowance was a quarter. So for me to spend two weeks of allowance on a record I didn’t even like was MAJOR. I was upset. So Eddie bought it back from me for a dollar!

Galloway: I was blown away the day I realized drummers could be leaders through Max Roach’s LP Members Don’t Git Weary (Atlantic – 1968). When did the idea of drummer as leader impact you?

Allen: Well, one of my childhood dreams was to be a Jazz Messenger. Of course, “somebody” already had that gig! I modeled a lot of what I did after Art then Elvin as well. What I loved about those two guys in particular is their concept was very much about the band….not “me-me” and solos. Some of my closest musician friends ride me to this day saying, “Carl, man, you need to take some solos.” That was never my thing. If I can play something that makes the band swing harder and the crowd’s feet tap harder, I’m o.k. with that.

There was a turning point for me in 1991. I was playing in a trio with (pianist) Benny Green and (bassist) Christian McBride. We did a 6-week tour opening for (drummer) Tony Williams’ Quintet (w/ pianist Mulgrew Miller, trumpeter Wallace Roney, saxophonist Billy Pierce and bassist Ira Coleman). I watched that man every night…the way he led that band, like, “This is me and this is the band”…but not in an egotistical way. He started every set with a drum solo…to warm up. The band never knew what the first tune was gonna be until he played a particular cue. It was different…not better, just different.

All of the drummers I gravitate toward including all the ones we’ve talked about plus Philly Joe Jones, Mel Lewis, Roy Haynes, Jimmy Cobb, Billy Higgins…these were all great musicians that just happened to be drummers. There’s a distinction. That’s what I’m trying to get to. One thing that humbles me every day is this: I’m 56. When I joined Freddie Hubbard’s band, he was 44. A couple of months ago I told Christian McBride, “Every day I wake up, I think to myself, ‘I’m still not playing at the level that Freddie was playing when he was 44’.” Christian said, “That’s deep, man.”

I was very close to Art Blakey. I remember subbing for him a couple of times with the Messengers – a high honor of my career and life. He was sick toward the end with cancer, as you know, but Art played up until the last minute (of his life) as did Elvin. Art was so small and so weak, his road manager would literally have to pick him up and put him on the drum seat. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think, “Man, this guy is about to fall over.” But when Art started to play, you would have thought he was 17 years-old. It was unbelievable. That epitomized what he always said: “Music is supposed to wash away the dust of everyday life.”

Galloway: Tell me about your relationship with Mr. Blakey.

Allen: When I first met Art, I was 18 and still living in Milwaukee where I’m from. I introduced myself but he didn’t pay me much mind…not that he should have. Then I moved to New York and I would go hear him with the Messengers. Shortly after that, I started playing with Freddie Hubbard in 1982. A couple months after, I was at Sweet Basil’s watching The Messengers which had my friends (trumpeter) Terence Blanchard and (saxophonist) Donald Harrison in the band. We were hangin’ after the set when Art motioned for me to come over. He said, “Terrence tells me you’re playing with Freddie. You know Freddie’s a former Jazz Messenger. Once a Jazz Messenger…always a Jazz Messenger.” He put his arm around me and said, “Since you’re playing with Freddie and he’s a Jazz Messenger, you’re now a Jazz Messenger.” Scott…I thought I was gonna fall through the floor. I remember that day like I remember the day my son was born. I walked away smiling and crying. I can’t even imagine what I must have looked like to every other man in the place. They were like, “You cool, bro?!”

This was before cell phones. I went to a pay phone and called my mother – collect – at 2 o’clock in the morning! She accepts the call and is like, “What’s wrong, boy?!” I said, “Ma! I’m a Jazz Messenger!” She said, “What?!” I told her again, she paused then answered, “That’s o.k., boy, just call me in the morning and I’ll get you a bus ticket. You know you can always come home.” She thought I had lost my mind and joined The Cult of Jazz Messengers!

Art was directly responsible for many moments that changed my life: listening to me, tough love…he really straightened me out.

Galloway: What’s the most profound example of Art giving a tough love lesson?

Allen: Art and I always had a very cordial relationship. He was always joking with me, putting me in a headlock and such. But one day I was playing with Freddie at The Blue Note in New York. We finish and as soon as I stand up, I see Art out of the corner of my eye. He just looked and motioned for me to come upstairs. Now I’m freakin’ because I didn’t even know he was there. I had been in Freddie’s band about three years. When I got upstairs to the dressing room, Freddie was standing at the door, the rest of the band was outside and Art was inside – alone – saying, “Come in here.” As I walk in, Freddie’s saying, “Art, don’t hurt him!”

The door closes and Art is pacing the dressing room, kicking chairs. Then he starts cursin’! He said, “Man, what are you doin’?!” I said, “What are you talking about?” He said, “I sat and watched you play a whole set! You weren’t orchestrating, you weren’t playing dynamics, you weren’t swingin’, you weren’t playing ‘with’ the band. You were lookin’ in the mirror, flirtin’ with the girls. You were not takin’ care of business! You were (expletive) up!” Before I could say anything, he continued, “”Now, I know what the problem is and I’ve already talked to Freddie about it. You’re tired of playin’ the same music. Do you know how long I’ve been playin’ ‘Blues March?’ Every time I play it I have to play it like it’s the first time…because for somebody in there, it’s their first time seeing me play it! You’ve gotten complacent! But I’m gonna tell you somethin’. You’re playin’ with Freddie Hubbard. There are many drummers around the world you’ve never even heard of that want your gig. If you don’t want it, get up and let somebody else have it!” Scott, I’m cryin’ at this point but Art does not let up. He digs in, “You need to understand that you’re in a fraternity now that includes Higgins, Max, Philly Joe, Cobb, etc. We’ve gone through too much for you to be able to make a living doing this. Right now, I don’t think I ever want to hear you play again. But if I ever do and you’re disrespecting the music like you did tonight, I’ll kill you.”

Scott, I had never seen Art like this. He wasn’t laughing or smiling. As soon as he said, “I will kill you,” he started to cry. He was like the strongest man on Earth to me. To see him cry really got to me. Within seconds, we were hugging and he went on to explain how important it is that every time you play, you have an opportunity to change somebody’s life. The bandstand is serious. When we opened the door, Freddie was sitting there cryin’, too. He looked up at Art and said, “Thank you.” To this day, I get emotional talking about it… The thing about it is he could have said nothing…and I would have just been another knucklehead that never ‘got it.’ But because he cared, he did that.

Every time I talk to young musicians, those men are on my shoulder, in my ear telling me, “Carl, tell `em The Truth.”

Galloway: How did Elvin’s approach to leadership differ from Art’s?

Allen: Art purposely got bands of all young kids. Elvin would get a combination of older and younger players together. His whole thing was “Each One Teach One.” He had a very matter of fact way of approaching the music. To him, there was no such thing as a mistake. I had separate conversations with Art and Elvin about the concept of a mistake. Art’s philosophy was, “A mistake is only a mistake if you don’t know what to do with that you’ve done.” Elvin’s thing was more Zen-like: “Everything that happens is supposed to happen…you just have to be aware of what happens in the moment.”

Someone once told me they were doing a recording date with Elvin. Listening to the playback, he didn’t quite know how to tell Elvin he had made a mistake. He was dancing around it like, “I think when we were tradin’ 4s…I don’t know but, at one point, I think you played a bar of 3.” Elvin wasn’t trippin’. He just looked at him and said, “Yeah, well…I owe you one.”

A. Scott Galloway

Music Editor

The Urban Music Scene

June 7, 2017